Of Valiant Empresses & Vagabond Princesses

During my college’s second year, in a class on India’s medieval histories, we were discussing the checkered personality of Mughal emperor Jahangir when a question arose on the weakness of his ruling years. With his interest in the intricate layers woven by the painters of the Mughal atelier, his fascination with the wonders of the natural world, and his undying love for wine, could he have truly ably governed an empire established by Babur, administered through tumultuous episodes by Humayun, and further ornamented politically, economically, and socially by his father, Akbar?

It had been twenty-two years since the prolific translator Wheeler Thackston published the English translation of Jahangir’s own words, immortalized in the memoir Jahangirnama. But a part of the analysis of the emperor presented in Thackston’s book continued to dominate the discourse of our undergraduate course: “A conscientious ruler and meticulous administrator of his empire, Jahangir lacked his great-grandfather Babur's adventurousness…His life was not filled with adventure or excitement, and as far as we can tell, he was never anywhere near a battle after his enthronement. He did not have the breadth of vision of his father, Akbar…â€

Inevitably, there were more queries. If it wasn’t him, then who held the reins of the reign? The name that emerged was that of Nur Jahan. Who was she? Mehr-un-Nissa (Sun Among Women) was born in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and fled with her noble family from Persia. She was wedded to Jahangir in 1611 and went on to become his twentieth and favorite wife, rechristened as Nur Jahan, the ‘Light of the World’. Once her name had surfaced, we embarked on our usual hunt, digging a range of sources, primary and secondary, to get glimpses of how Nur Jahan had been remembered.

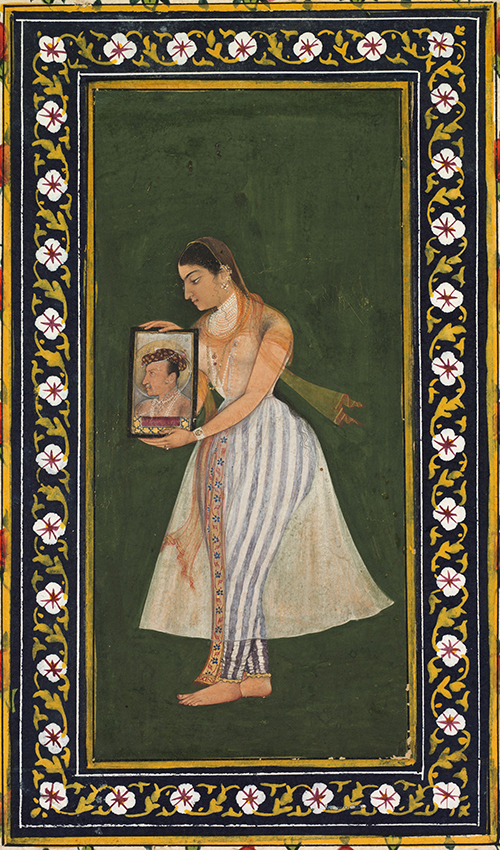

Nur Jahan holding a portrait of Emperor Jahangir | 1627 | Attributed to Bishandas | Cleveland Museum of Art

What was quickly realized was that most records contended that Jahangir’s political skills were notably weaker compared to other emperors, claiming he relinquished all political authority after his marriage to Nur Jahan six years into his reign. Following this was the argument that the throne was governed by a junta comprising Nur Jahan, her father Itimad-ud-Daula, her brother Asaf Khan, and possibly Prince Khurram. This belief was so strong that in his 1922 History of Jahangir, Beni Prasad described Nur Jahan as having a “restless brain†that could only be satisfied by “unquestioned dominion†following Jahangir’s illness. Contemporary records by traveling-chroniclers, such as those by Thomas Roe and Peter Mundy, depicted the queen as “stubborn†and “manipulativeâ€.

However, these arguments did not seem to capture the complexity one would expect from ‘history’, one that was lived, and was inherently multilayered. Instead, such views reflect ‘History’ as studied through a single lens, which may often lead to intense perceptions that oversimplify epochs that were far more convoluted. And thus, it was refreshing to come across historian Ruby Lal’s book, Empress, an animated and rich biography of Nur Jahan. It was in this text that Lal established her as an “astute politician, governing as co-sovereign along with her husband.†But what was most important is that Lal, as she followed the footsteps of Nur Jahan, saw her taking paths that went beyond ones that ultimately tied her remembrance with Jahangir. What had irked many of us during our classes was that Nur Jahan, the person, only emerged in discussions when one was pondering over Jahangir, the personality; that in the emperor’s ‘weakness’ was located the empress’ ‘wickedness’.

But Lal had trudged into the unfrequented corridors of history to pen down a biography of a woman who held a multifaceted position at the Mughal court. While defining the contours of the earlier works on the queen, Lal wrote that there had been “no palpable sense of the anger or playfulness we’d expect of a living woman, no details about her support of Jahangir, her deep investment in the life of the empire, her political maneuvers and countermaneuvers, her raw ambition, her vulnerability as well as her strengths, or the very human way in which she fought to build and preserve her husband’s and her own sovereign rights.†And with this book, Lal attempted to undo all of that and she brought to life the story of Nur Jahan with the nuance it deserved.

And Lal has done it again! This time, she has gone further back to tell the tale of the daughter of Babur, the founder of the Mughal House. Lal's latest book, Vagabond Princess, focuses on the inspiring Gulbadan Begum and her world of exciting voyages and remarkable writings. Earlier in 2024, during a session at JLF London, Lal spoke about her fascination with Gulbadan, the princess born in Kabul in 1523. At the age of six, Gulbadan became the first girl to travel in a caravan along the Khyber Pass. She lived in a mansion in Agra across the Yamuna until the age of seventeen and was very close to her half-brother, Humayun, who would go on to become the future king.

Gulbadan wrote the Humayunama in the tradition of qissa-khwani, that of the storytellers. As Lal said in London, Gulbadan’s chronicle has been traditionally dismissed on very weak grounds, one of them being her dates, in some instances, being incorrect. Responding to this, Lal said: “This is a medieval chronicle. This is not a modern imposition of dates. It is a stream of consciousness style which is really quite extraordinary!â€

To share stories upon stories found in Gulbadan’s immersive account and to paint a vivid picture of her compelling life and times, Lal will be joining Reza Aslan at the 10th spectacular edition of JLF Colorado. This is a session not to be missed, so make sure your spots are secured for a discussion that will tangle yet enrich our views around the past!

Sources

- Lal, Ruby. Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2018.

- Lefevre, Corinne. “Recovering a Missing Voice from Mughal India: The Imperial Discourse of JahÄngÄ«r (r. 1605- 1627) in His Memoirs.†Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 50, No. 4 (2007): pp. 452-489.

- Prasad, Beni. History of Jahangir. Volume 1. London: Oxford University Press, 1922.

- Thackston, Wheeler. M. trans and ed. Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Vagabond Princess | JLF London 2024

Leave a comment