Tune in for narratives critical to our times. Listen, ask and seek answers.

Watch Now

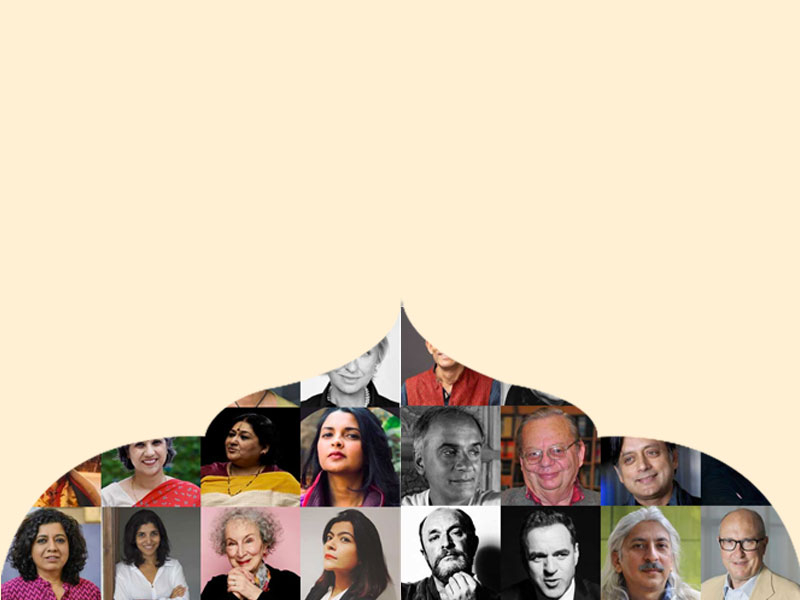

Stories that persist after we’re gone - Elif Shafaq with Janice Pariat

Last weekend at JLF Brave New World, Turkish-British writer, essayist and women’s rights activist Elif Shafak spoke to author Janice Pariat about her latest book, ‘10 Minutes and 38 Seconds in This Strange World’. Pariat initiated the session with the topic of the writer’s dilemma during a lockdown. Elif Shafak empathised, “I find myself going through a rollercoaster. In this existentialist angst that we are going through, on some days you realise that books, literature and empathy will matter even more.†But on certain days, like others, Shafak is haunted by feelings of inadequacy: “What difference does it make whether I find the perfect synonym for this word, when people are dying in tens of thousands, and when there is so much injustice and inequality around?†On the topic of the writer’s role in bringing out obscure narratives, Janice Pariat asked Shafaq about aspects of her novel and her conviction that apart from chasing the stories, a novel “must also pay attention to the silencesâ€.

‘10 Minutes and 38 Seconds in This Strange World’ sums up the recollections of its protagonist, Leila, a sex-worker, during the narrow window of consciousness right after her death. The structure, admitted Shafak, was challenging, but she was intrigued by the scientific study which showed that brain activity persisted in dead patients for about 10 minutes after the heart had stopped beating. “The part of the brain in charge of long term memory is the last to shut down. Then what do the dead remember- the good things in life or the bad? What remains from a whole life lived, and how do you compress it in 10 minutes?†While that was her starting point, Shafaq’s desire to bring the “periphery to the centre†was what spurred her on. “The need to give voice to the powerless,†she said, “and to empower the disempowered is the underlying current in my work.†She explores this aspect in her book through Leila’s relationships with her friends, a motley group of misfits- a Lebanese refugee with serious health issues, a trans woman and a victim of human trafficking among other characters.

Turkey, Shafaq highlighted, was a fertile ground for developing such stories- although it is a country with a long and rich history, its inhabitants don’t necessarily possess a “solid, strong memoryâ€. Her description of Istanbul would find resonance with Indian listeners: “In fact, it’s the opposite. It’s a society of collective amnesia, of forgetting. In a setting like that, it’s the writer’s responsibility to remind people of forgotten voices. Memory is a responsibility.â€

In our broken societies, friendships become all the more essential to help navigate complexities, and with the portrayal of Leila’s friendships in the book, Shafaq aimed to remind her readers that we all have two kinds of families. The biological family, which if kind and tender, should urge us to count our blessings, but not everyone is lucky. “As you keep living, there’s going to be a second family, composed of friends; they can’t be dozens and dozens but even if they are a handful, they are our true companions. They pull us up when we fall down- I wanted to honour and celebrate that.â€

The book has been praised for its descriptions of Istanbul and its streetscape, and for breathing life into its diverse characters. What process does Shafaq follow to paint such vivid frames in her writing? “As a writer,†she said, “we need to be readers but we need to be listeners as well. I was an outsider in Turkey, and I think that made me more observant.†To illustrate her point, she recounted a fascinating incident- when in Istanbul, she lived on a street with an eclectic population of ethnic minorities, LGBQT individuals, bohemians and a transgender community. Once they were hit by an earthquake, following which, differences between people seemed to have somehow evaporated in the face of crisis. “The grocer who lived on the street, who never greeted a queer person, offered a cigarette to a trans person and they both sat smoking next to each other. The next day, however, he went back to being bigoted,†she said.

Although her books are tinged with memories of Turkey, Shafaq admitted to considering herself a global citizen and being uncomfortable with identity politics. “I can understand it as a starting point, but it can’t be where we end up.†She underscored the presence of identity politics in the publishing world, contrary to what one would expect. “An Afghan woman should be able to write science fiction, and not just be expected to tell ‘real stories’ about Afghan women. Why reduce ourselves to these boxes? I am attached to Istanbul emotionally, but I also feel close to the Balkans, and I am also a Londoner, and quite European in my values.†Taking it further, she also spoke about the importance of interdisciplinary conversations and a need to read across cultures. In our world, where knowledge can be extremely specialised, one wonders if we have shifted too far away from a synoptic view of things. “How is it possible that so many experts got so many things wrong- whether it be Brexit, the financial crisis or Trump’s election?†Shafaq suggested that it was because we tend to get ‘atomised’ in our work and worldview. She concluded her conversation with Pariat with her thoughts on how to challenge ourselves intellectually: “An economist could learn from poetry, what if a neuroscientist referred to film-theory? We need, more than ever before, a cross-pollination of ideas.â€

Leave a comment