Tune in for narratives critical to our times. Listen, ask and seek answers.

Watch Now

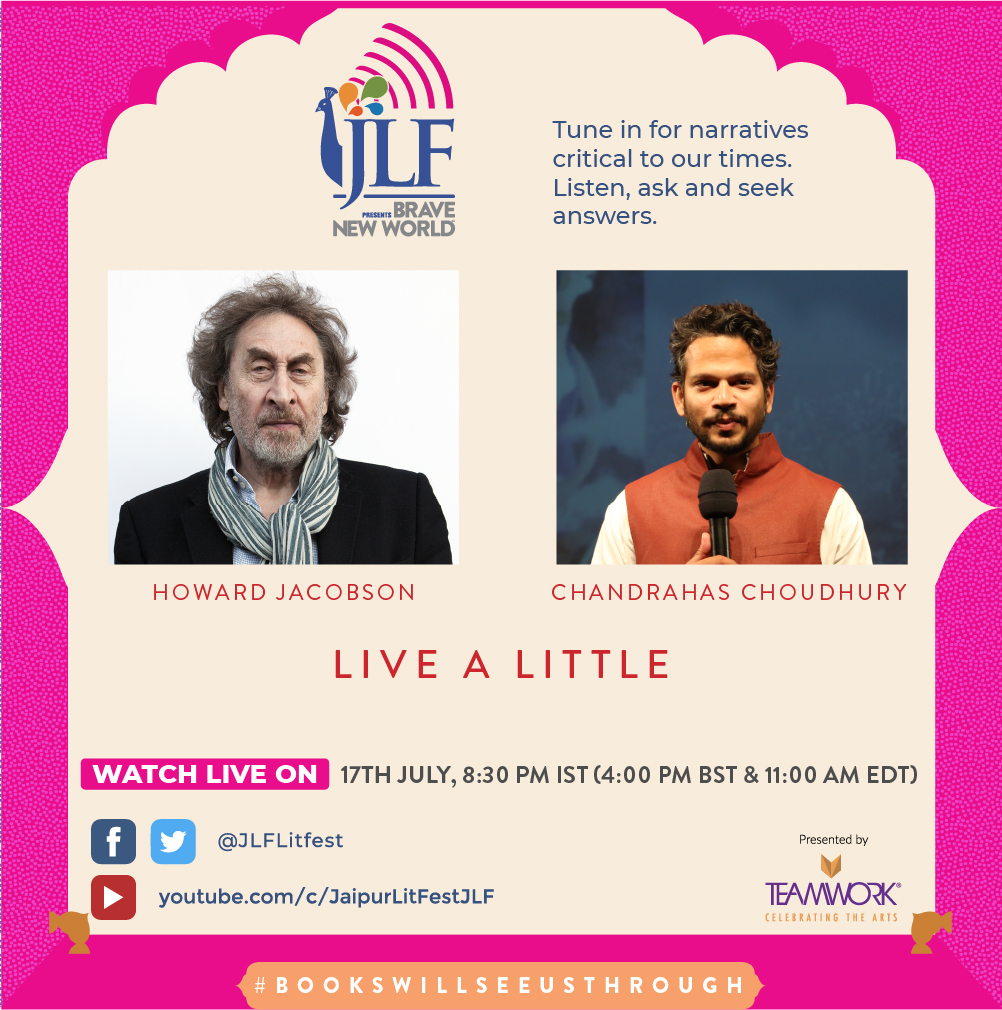

Live a Little

“Don’t let this get out of this room, but I am actually quite tame.â€

I could imagine every member of the audience laughing along with Mr. Jacobson as he replied to my slightly impertinent question, “What peculiarity have you been indulging in, in this period of isolation?†Tame and him? Who’d believe that? But my day was made hearing this generous man laugh at my question and then reply with his signature dry humour.

A session crackling with wit and whimsy, the Man Booker awardee, Howard Jacobson held us captive with his spoken words as he chatted with Chandrahaas Chowdhury, at #JLFLitfestBraveNewWorld last week.

“My life hasn’t changed much with the lockdown. I still write in solitude, hardly meet anyone and I wash my hands very often. In fact, writing is like an inoculation against the fear of the virus.†Describing his current project – a memoir of his own, he said that everyone, including a six-year-old child has memoirs that could be written. But he had got down to it only now at 77, because it felt unbecoming to have written it earlier. “I highly recommend writing a memoir if you don’t have a novel to write. It gets rid of all your fear and anxieties and someday someone might read it!â€

Mr. Jacobson’s writings have drawn generously from his own life and experiences – his Jewish upbringing in Britain, his relationship with his sibling – all of which leads to him being unsure if “while writing my memoir, I am remembering my actual life or am I remembering all the novels that I have written about my life. I think I am factualising fiction! My book should be called Unreliable Memoirs.â€

Later in the conversation Mr. Jacobson notes that he is currently agonising about the appropriate name for his memoir. “If anyone has any suggestions, do send them in. I will send a pound in an envelope in return!â€

Talking of his last novel, ‘Live a Little’, that narrates the love story of nonagenarian Beryl with the 91-year-old Shimin, he says that the title of the novel has become prophetic in these times. Because “little†is what we may well have left. Commenting on a world that’s increasingly fraught with rigid ideologies, he feels never has fiction been more necessary than it is now. “Novels with their lies, ironies, complexities, uncertainties will stimulate in these times when people are so set on their ideas. I’d say read books written by people you disagree with. People who are least like you are whose books you should read first. Don’t read what you agree with.â€

And where do we stand with comedy now? Is laughter an endangered emotion? His response is immaculate – freedom of speech is symbolised by the joke or comedy. In the present world, humour is threatened by homogeneity. And it’s the novel that’s the perfect antidote, the great solvent for sanctimony, as he describes it. “For a novel, nothing is sacred.â€

Describing his journey as a writer he says self-deprecatingly, “When I was young, I wanted my writing to be aristocratic, aloof and elegant. I wanted to be a modern Henry James. But I was pathetic at that. Then I wrote a satirical novel and did everything I didn’t want to do with my writing and that worked. Now, as a satirist, I am never out of work.â€

Reflecting on his oeuvre, he says that with every novel, the last one becomes a piece of history. “It’s best to be like an unfaithful lover, move on to the next one and don’t re-visit the past.†I could see reflections of his avant-garde creation, ‘The Act of Love’, in the pronouncement that dwells on the idea that loss is intrinsic to love. I thought of the self-destructive and perverse Felix Quinn from that novel, throwing his beloved wife Marisa into the arms of another man, because he imagines that his happiness lies in her infidelity. I had got a copy of this book signed by the gentleman himself at the last Jaipur Literature Festival and he had remarked with surprise to see the book of my choice, “Not many people find this a favourite.†But that’s the irony, the unconventional plots that emerge from his pen keep his fans hooked.

Mr. Jacobson may call himself conventional but if there is a novelist who can create a torture garden that combines the corrosion of jealousy with luscious passion, its him. Right at this moment, sitting in his home in Soho, in isolation, this literary genius is possibly penning down ideas that will shock and pleasure us in equal measure, much like his sado-masochistic characters. Not for a moment do I believe that Howard Jacobson could be defined as “tameâ€.

Leave a comment