Tune in for narratives critical to our times. Listen, ask and seek answers.

Watch Now

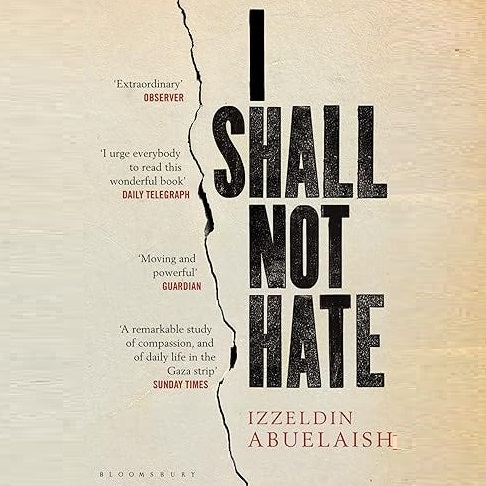

I Shall Not Hate

Every few days, I sink into despair at the on-going massacre of innocents in Gaza, and now in Lebanon.

How - I cannot answer, even after spending hours with Dr. Abuelaish - does he not allow himself to fall into the same despair?

A Palestinian doctor, Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish wrote of the death of his three daughters by Israeli bombs in his book, I Shall Not Hate, published in 2010. It was a difficult read then, but also inspiring. Reading it again this summer, in preparation for an engagement with him at JLF New York, was deeply disturbing. On a stage in Brooklyn, he recalled words from his book:

“If I could know that my daughters were the last sacrifice on the road to peace between Palestine and Israel, then I would accept itâ€.

But they weren’t the last, and after the cycle of violence and revenge was unleashed again last October, thousands of daughters have been sacrificed, thousands of sons, thousands of young couples, who will never know the trusting embrace of a child.

The region is locked in the embrace of revenge and counter-revenge, a cycle of hatred which Izzeldin swore to eschew, even as he fought back the tears when he recounted the events of January 2009.

On January 14th, Izzeldin woke up to find the barrel of an Israeli tank bearing down on his home in Jabalia camp. This must be a mistake; he was a gynaecologist working at a leading Israeli hospital, and the Israeli army - the most moral army in the world they used to maintain then - was also the best informed army in the world. They knew it was his home, he knew they would not target him for harbouring militants, which would be the excuse for innocent deaths. He worked the phones, the first call was to the Israeli TV journalist Shlomi Eldar, for whom Izzeldin had become an eyewitness to what was happening in Gaza. He spoke to a radio journalist, then an army spokesman called; after he had understood the situation, Izzeldin watched the turret swivel away, reluctant almost. The tank rolled down the street.

That evening, Izzeldin and his family offered prayers for their survival. Around them, the city was under siege, food supplies choked, water lines dry,

“Entire neighbourhoods being obliterated with bombs and rockets… as though to erase the evidence that people had ever lived there - that old people and small children, teenagers and parents walked on these streets, slept in these houses, ate together, bowed to the east, and kneeled to pray on their mats.â€

The siege was unremitting. Two days later, in the early evening of January 16th, it happened:

“There was a monstrous explosion that seemed to be all around us, and a thundering, fulminating sound that penetrated my body as though it were coming from within me. I remember the sound. I remember the blinding flash. Suddenly it was pitch dark, there was dust everywhere, something was sucking the air out of me, I was suffocating.â€

The explosion had come from the bedroom of his daughters. Four lives lost in an instant, three of his daughters, and their cousin. Two other children's lives hung by a thread. They would never be saved by the tattered medical infrastructure in Gaza.

Izzeldin phoned Shlomi Eldar, who was live on Channel 10, and didn’t answer, because he was just about to interview the Israeli Foreign Minister. When Izzeldin’s number came up again on his phone, he took the call, wondering if this was the right thing to do, but then gripped by the abject horror of what he was saying. The show editor spoke into Shlomi’s earpiece, asking him to move the microphone closer to the phone. The conversation went live on television*:

“Oh God, they killed my daughters, Shlomi. I wanted to save them, but they are dead. They were hit in the head. They died on the spot. Allah, what have we done to them? Oh God.â€

Izzeldin appealed for ambulances to be rushed to the border, Shlomi excused himself from his anchor’s desk, and the camera followed him as he worked the phones - to military checkpoints, to hospital directors and ambulance drivers. Shlomi accompanied the ambulances to the border, from where Izzeldin’s daughter was transferred to an Ashqelon hospital, and his niece airlifted to Tel Aviv.

Both lives were saved, but around them the bombs still dropped, the rockets still whizzed, and the people of Palestine screamed, from fear and loss. Fifteen years, and forty thousand lives later, it’s as if nothing has changed.

Izzeldin’s family had fled their ancestral farms in Palestine to the Gaza strip in 1948, to escape the Nakba, the catastrophe of 1948, when Israeli nationalists swept into thousands of villages and forced them from the farmlands and homes. The move would be temporary, his grandfather believed, and they still hold the paper titles to the land. But it is now called the Sharon farm, the title transferred to Ariel Sharon*. The same Ariel Sharon who decided that their street in Jabalia camp should be broadened, so tanks could easily pass. The same Ariel Sharon who destroyed their tiny Gaza home.

Izzeldin never knew the family lands. The only life he knew was that of a refugee - disenfranchised, marginalised, and suffering. By the age of eight, he went to work, to help feed the family; by the time he was a teenager, he was doing hard manual labour on Ashqelon construction sites - every Friday, every holiday. But he also had to come first in school, his mother insisted. That was his only way out of the camps - in his case, to medical school in Cairo, on a full scholarship.

“I maintain that revenge and counter-revenge are suicidalâ€, Izzeldin repeated, under the bright lights of our New York stage. If this was true in 2010, when he wrote his book, it is even more true now. But those men, he believes, who meet in the sanctity of government offices, are not serious about human life and the turmoil in Gaza. America, he told our audience, is not Israel’s best friend - only its neighbours can be. Muscularity, armed by an unending supply of American bombs, can never bring about peace.

In his book, Izzeldin appealed to readers to vote regressive politicians out of office. Aside from Netanyahu, the politician who can do the most to bring about peace in the region is the President of the United States. But Biden has given Netanyahu a blank cheque of kilotons of bombs. Whether Trump or Harris, I don’t see that changing, this November. As my friend Navtej Sarna* wrote in a column earlier this week, Israel is eyeless in Gaza, “raging in futile circlesâ€, from which no good will come.

How do you hold on to hope, a lady asked from the audience. Even as the tears streamed down his face, on the JLF stage in Brooklyn, Izzeldin renewed his pledge to the path of peace:

“It is a question of accountability. When I visit the graves of my daughters in Gaza, I must tell them that the answer to their death is not more death, but love, and peace, and I will work towards that as long as I live.â€

This is alchemy, I had told Izzeldin the first time we chatted: your will to transmute hate to love.

You humble all those you meet.

Go in power, go in peace.

References:

The telephone call on Channel 10:

· Ariel Sharon, Army General, and 11th Prime Minister of Israel:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ariel_Sharon

· Navtej Sarna

https://www.theweek.in/columns/navtej-sarna/2024/09/28/when-widows-howl-and-orphans-cry.amp.html

· Daughters for life, the foundation established by Dr. Abuelaish, for the education of women in the Middle East:

Leave a comment