Tune in for narratives critical to our times. Listen, ask and seek answers.

Watch Now

How Can the Sacred be Sensuous?

“For most people, bhakti is that intense personal devotion towards a chosen deity and there are many strands of it and one major strand of bhakti is to extoll the sheer physical beauty of the divine.â€

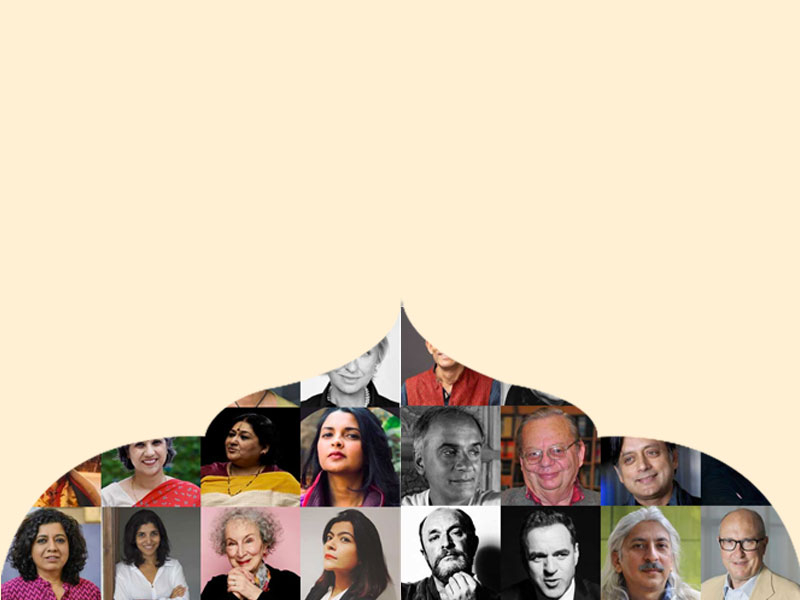

In an enthralling session at JLF Brave New World, renowned art historian Vidya Dehejia engaged in a captivating discussion with William Dalrymple, reexamining the idea of the 'sensuous' in Indian art from the pre-modern period. Dehejia emphasised that through the ages, Indian artists portrayed gods and goddesses in their own image, expressing their devotion through sculptures that celebrated the divine's physical beauty.

Dehejia drew from three main sources: hymns of saints, courtly literature, and inscriptions. “All of these sources point to the fact that one easy way to approach the divine is through revelling in the sheer bodily beauty of the god and goddess and adoring that divine body,†said Dehejia.

Dehejia shared powerful hymns from poets like Appar, which beautifully expressed the desire to behold the physical beauty of divine forms. She brought these verses to life by reciting them in Tamil, conveying the intensity of love and devotion carried in these ancient poems.

The discussion also touched on the placement of sculptures in museums, with Dehejia expressing her displeasure with obstructed views of sculptures due to poor display arrangements. She highlighted the beauty of these sculptures and their ability to captivate viewers with their alluring qualities. Dehejia also lamented the underappreciation of art in today's materialistic world, where many historical sculptures sit in dusty museums.

Dehejia and Dalrymple compared Indian art with sculptures from Ancient Rome, noting similarities in bestowing physical beauty upon the divine. However, Dehejia pointed out that India expressed this love in a unique way through a vast corpus of poetry and writings, while Rome lacked a similar tradition.

Reflecting on history, Dehejia urged people to imagine a time when seeing these sculptures was a rare and overwhelming experience for devotees, as reproductions and easy access to images did not exist!

Leave a comment