Machines Like and Unlike Me

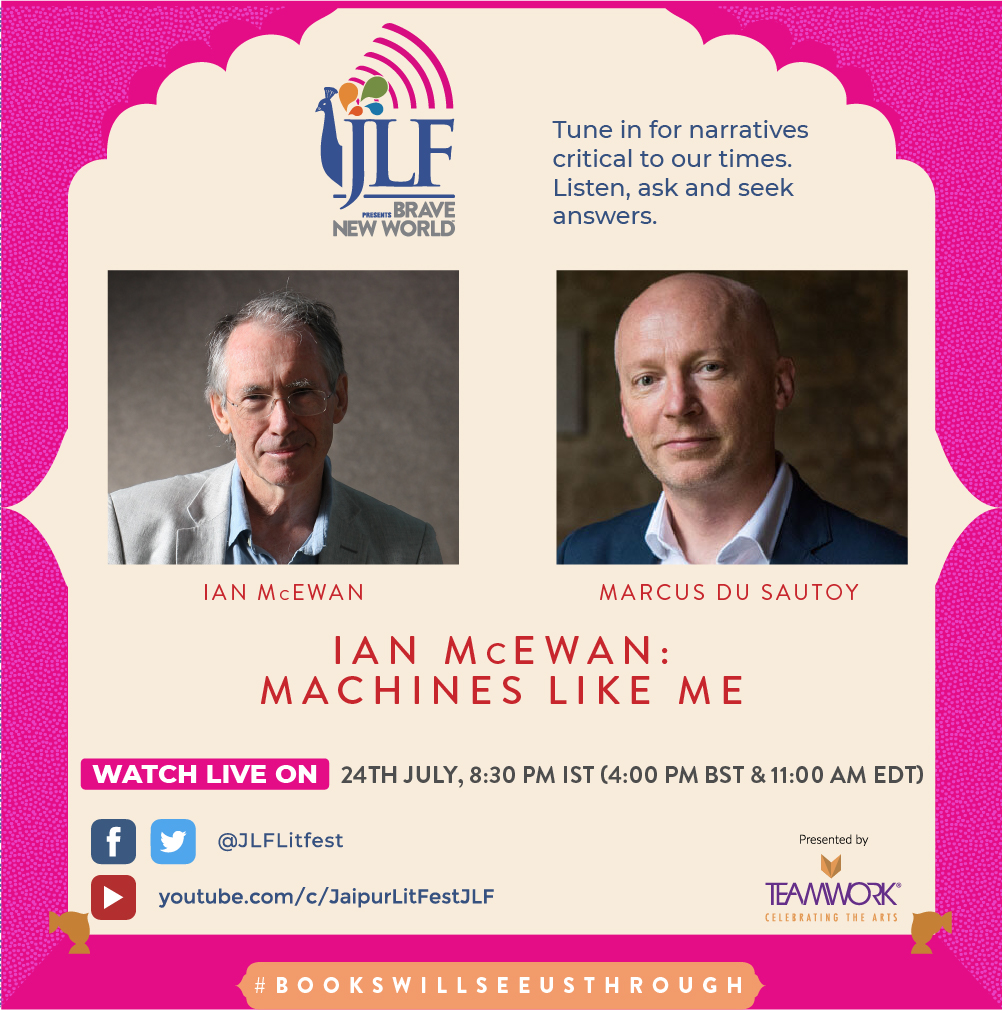

It was a Saturday evening. I dimmed the lights, powered up my laptop, and poured myself a glass of bubbly. What was I celebrating in this extended state of lockdown? The presence of two intellectual giants in my living room! JLF Brave New World had novelist Ian McEwan and Oxford professor Marcus du Sautoy in conversation and I felt that called for a celebration. So I raised a solitary toast (as the three boys that make up the rest of my household were in the next room, embroiled in watching England and West Indies battle it out on an empty cricket field in Manchester) to the boundless power of human intelligence. Or wait, was it Artificial Intelligence? Were they the same or completely different?

When I had seen JLF Brave New World’s programme for that week, I had felt it was serendipitous that I had just downloaded ‘Machines Like Me’, McEwan’s retro-futuristic 2019 book, on my kindle, and volunteered to write on the session. McEwan’s fascinating duality – his mastery over a complicated web of human emotions along with his preoccupation with alternate realities – makes him, for me, one of the modern world’s most compelling storytellers. And so I settled in for a long listen.

As Marcus said in the beginning, laying to rest questions why JLF had paired a scientist and a novelist together – “Ian loves science” – anyone who has read ‘A Child in Time’, ‘Enduring Love’, ‘Solar’, and the most recent ‘Machines Like Me’, would see the criss-crossing of a deep involvement with science and a nuanced understanding of human frailty.

On asked why he was so interested in science, McEwan recounted how as a “layboy”, science had always fascinated him, and under the rather strictly compartmentalised English education system, which makes one choose between science and humanities at the age of 16 (much like the Indian system, I thought!), he had gone with English on a whim as the English teacher had perhaps been a more attractive proposition. But “always with a look over his shoulder” on what could have been – which I realised fiction gave him room to explore. A part of his “mental furniture”, he said, was to think scientifically.

“Why now this book on Artificial Intelligence?’ asked Marcus. “I have been living with it for years,” said McEwan. His obsession with AI is long-drawn; in the late 70s and 80s, he had researched heavily and written a TV drama, set loosely around Bletchley, and in 1980, had come his BBC production, ‘The Imitation Game’ long before the 2014 film of the same name on Alan Turing was released, starring Benedict Cumberbatch. McEwan’s ‘The Imitation Game" is about a Cathy Raine, who becomes one of the many Bletchley Park women and who, in complete ignorance of what she is really doing, transcribes signals that feed the electronic behemoth that Alan Turing (here named "Turner") and other men are nurturing.

While working and researching on humanoids, McEwan said he felt that the “ancient dream, the golem” that figured in ‘Jason and the Argonauts’ was always a bit out of reach. The robots and androids he saw on TV, (“they weren’t even powered with batteries!”) just didn’t get it right – he wanted to understand what it was to live close-up with an artificial mind and to see if it had human consciousness and thus was born Adam, the humanoid in ‘Machines Like Me’.

‘Machines Like Me’ belongs to the cavernous reaches of science, speculation and fiction noir at whose cross section, in a bleak, post-alternate-reality Falklands War London backdrop, are three central characters fixed in ménage-a-trois-conundrum of emotions and secrets. Charlie, broke, amoral, inconsistent; Miranda, secretive, beautiful, never letting on much and Adam, the well-endowed, supremely intelligent robot who knows much more than he lets on. Adam is clearly the moral superior, who begins as Charlie’s and Miranda’s digital “baby”, but soon takes on the pivotal role. The book naturally looks up to Turing, while delving into the complex territory of the rights and thoughts that can be assigned to Artificial Intelligence, a question which Turing had prophetically asked in his 1950 seminal paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence".

When asked what made him make his android so very human, McEwan said he wanted to make his AI – Adam -a better version of ourselves. The “ancient dream”, which even the creator of Frankenstein had set out to fulfil, of making and replicating ourselves, has this intrinsic dilemma: when we look into a mirror, we ask ourselves, can we make humans who are nicer than us? Can we use every “priest and shaman and moral philosopher” we can find to create a foolproof ethical code by which the machine we make would act in accordance with a more correct touchstone of morality?

“We know how to be good,” said McEwan and admitted that we have a huge problem with being good all the time. What if we gathered all our goodness and created an artificial human who would live by a reasonable moral and ethical code? “I really wanted someone absolutely human-like to explore the boundaries of difficulty, interest and possibly even tragedy that lie ahead of us.”

Intense questions these. They jostled in my head with disquieting thoughts about the AI future. Where would it all end then? As McEwan said, “We may deal ourselves out of the game!” In making a generation of androids which makes yet another, we may perhaps just become irrelevant by our own inadequacies. Why are we then embarking on this journey was the question which incessantly beeped in my own very non-android head. Have we reached a point of no-return already in our AI saga? Too frightened to think further, I took an even larger sip of my sparkling Rosé!

McEwan went further and told Marcus du Sautoy that we may think we are the most intelligent creatures on Earth but we could just be the second-best! In fact, the idea of making an artificial human is like holding up a “giant mirror” to oneself to explore the boundaries and edges of what being human means. I reminded myself that the creators of AI are still us, and as if on cue, McEwan remarked the point of AI is actually to demonstrate what a remarkable piece of work man or woman is. AI could teach us more about ourselves – Marcus commented that was indeed Turing’s original goal – to create AI in order to understand what makes “us” intelligent.

At the heart of ‘Machines Like Me’ are themes of moral dilemma and revenge, feelings which the human characters are deluged by and which the humanoid is devoid of – paradoxically, because his moral universe is absolute – there are no ambiguities, no back-stories, no larger contexts. Does this make his moral precinct ruthless and cold? Which brought us to the central and philosophical question – can these creatures who are governed by a power button “feel”?

Marcus mentioned at this point about a non-fiction book he too was writing on Artificial Intelligence – which examines whether AI can take over what is known to be uniquely human, that which distinguishes between our individual “inner worlds” – creativity. He quoted a passage from ‘Machines Like Me’ in which Adam says, “When the marriage of men and women to machines is complete, this literature will be redundant because we will understand each other too well.” McEwan was quick to clarify this was Adam’s view, not his, and Adam is speculating at a very adolescent stage of his intellectual life of a time when our brains have implants which are connected to the internet, thus allowing us full access to each other’s minds. The novel, according to McEwan, is born of human misunderstanding and friction, apathy and wrong-doing. And so Adam’s idea is that once we understand each other perfectly, there will be no room for human folly or the novel. “It’s a rather extravagant theory,” assured McEwan, as he anticipated the human civilization to continue being the “fantastic mess” that it is and novelists “being gainfully employed for millennia.”

Whew! I heaved a sigh of relief. I shall sleep better tonight, knowing that. But of course, I will need to finish the remaining pages of my book to figure what Adam really meant...

Leave a comment